At the Plum Grove

2015

At the Plum Grove - Research

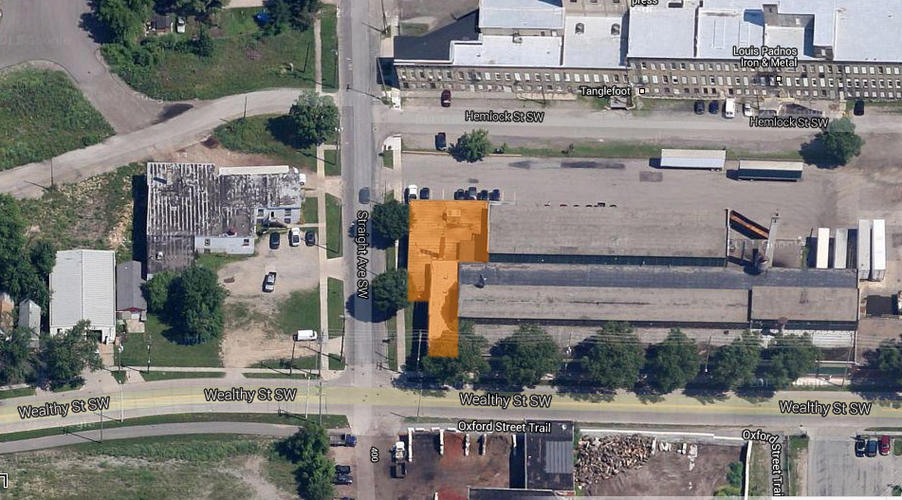

October 6, 2015Our inquiry at the Straight Street at Wealthy studio, located in Grand Rapids, began in scatter shot like all studio inquires begin. It wasn’t until we learned of the indigenous plum grove in the area that the studio gained a cohesive framework. As we continued to research we would continually revise our stance. For instance Grand Rapids is itself a translation of Gaa-ginwaaijwanaang (At the place of Long Rapids) from Ojibwe. Much in the same vein that Turtle Island is used to name North America. Which is used because it synthesizes both indigenous and colonizer cultures; by translating the former into the latter. As settlers; we are never off the hook. We realize it is always an ongoing and open relationship. We do not have the comprehension to be the authority on this. We realize the need to confront and delink from the colonial matrix of power. Throughout this project we recognized the need to change our participation in systems of inequity and domination. To further this point, all our work is provisional and available for further engagement.

Our research to date has only come from settler sources, namely Charles Belknap, once Mayor of Grand Rapids, two versions of his book The Yesterdays of Grand Rapids. the final being a hollow version of the draft. As we continued researching our terminology shifted from plum orchard to plum grove to finally, At the plum grove. This signified the importance of indigenous sovereignty, because there is a continuing need for disengaging from colonial terminology of indigenous culture.

As we had very little concrete information about this place, our imaginations went wild. It truly became a myth, and an utopian vision of ecological and social harmony. At points it became apparent that we were operating within nostalgia.

During our research one of the studio members, Morgan Hayden, wrote a poem using imagery of the plum grove. Poem is published below. The sharing of this poem was a major development in the studio, as it made more apparent the situation we were in. Other notable things were, the looking for plums in the area which is considered a food desert, and a search for the location of the plum grove, looking for the remnants.

“Sometimes, when the seaflowers blow blue

I’ll fish out sticky plum pits from the bottom

of the grocery bag. There

used to be an orchard where

that empty building is now.

It wasn’t any orchard, you know,

moss moved over the ground,

concentric circles mirroring the

movement of bodies

turning and twisting in space, offering

all their sweetness to the sweetness

of the wild plum trees.”

Below are the final and draft of a selection of Belknap's The Yesterdays of Grand Rapids, the former preceding the latter. The two have strikingly different representations of the plum grove. The draft being story and myth driven while the final being objective and factual.

THE INDIAN PLUM ORCHARD

(as published in The Yesterday's of Grand Rapids)

Not until the early seventies did the last trace of the Indian plum orchard, on the west side of the river below the present site of the Wealthy street bridge, disappear. Then it was slashed into log heaps with other bottom land trees and burned in order to make pasture.

This orchard was well known to early day people. Plums grew in profusion on river bottom lands--but these red, yellow, and blue plum trees were in circles about a moss-grown basin of about two hundred feet. It was believed to be an assembly place for Indian ceremonials; very early white men told of corn dances held there.

I do not know who cleared away the orchard. My memory is of the wonderful training place its moss-grown ring made for young acrobats and of delicious plums and wild grapes which we carried away by the basketful for our mothers’ winter supply of preserves.

Then the crabapple, a sociable little tree, had grown up in any vacant spot, not particular about location; in the spring its pink blossoms grew so thick that they crowded each other off the branches. If a boy tore a hole in his trousers the tree furnished thorns to mend the tear. The man who named this fruit had never tasted the jam that mother made with maple sugar and set away in jars in the cellar or he would have found a better name it than “crab.”

When I first played there in the fifties, there was under a dense growth of vines, a driftwood wigwam with a hold in the peak to let out the smoke. A pole bed with swamp grass, fit only for a homeless dog, occupied one side.

One day there came to our home on Waterloo, now Market street, an Indian women with baskets to trade for food. She told my mother that her daughter with a newly-born babe was lying very sick in the plum orchard wigwam.

Mother, in company with a French woman who lived near Sargeant’s pond, took a basket of food and went with the squaw in her canoe.

The French woman brought the little pappoose back with her. Her own house was so full of children that her old man slept in the stable, but other nearby mothers gave baby clothes and furnished catnip tea and Van, the milkman, left an extra dipper of milk every morning. That little pappoose had lullabys in Irish, French, and English and if it had stayed until it had learned to talk the dialect of the neighborhood its Indian mother would have disowned it. But one day when the mothers were having a quilting bee she came and carried it away, strapped in a blanket to her back.

Leading to and from the plum orchard were well worn trails to the hills on the west and up and down the river banks. The Black hills across the river, the council pine up the stream, may have been the guide to the orchard, but just what was the Indian belief or mystery of this place or why the trees were planted in circles of red, blue, and yellow, will probably never be known by the white man, but it must have been common ground to the Indians for long years before the first white settler came to the valley.

There was no evidence that it was a ceremonial place, although it was within half a mile of the Indian mounds.

THE INDIAN LEGEND OF THE PLUM ORCHARD

(draft of chapter in The Yesterday's of Grand Rapids)

Twenty years ago this tradition was told (to) me by an Ottawa Indian women. At the time there grew near the banks of (the) Grand River, about where the west end of the commonwealth Railway bridge now is, the Indian Plum Orchard, as it was well and commonly known to the early residents of the Grand River Valley.

While all the river banks of the valley were lined with wild fruit trees and vines that nature had provided for both man and birds. The plum orchard had more the touch of man as though some gardener had planned the setting. Plum trees in alternate rows of red and yellow fruit grew in rows about a circle some two hundred feet in circumference slightly slooping toward the center.

The Spring floods covered all this low river bank country and when the waters receded, leaving a river sediment–there grew in this hollow only a fine moss, while all the banks outside the circle of trees were covered with a growth of blue violets, Indian pinks and countless others of God’s wild children. None ever intruded upon the circle, which with its carpet of moss, made a fine circus ground for the boys who were growing up in this new “white mans” country.

Many an early settler in the seclusion of the circle hung his shirt on the branch of a plum tree and went to the river for a swim in the water clear as the sky on a sunny day; then back to the shelter of the trees to roll and dry in the soft fragrant moss that nature had seemingly provided for this purpose.

Regularly with the seasons came the blossoms on trees, the fruit and the autumn days when the folks of the village came with their baskets to the Indian plum orchard for their Winter supply. Cultivated fruits were scare and wild plum-grape and crabapple for preserves and jelly were in demand. Gathering grapes from the tangled vines of the tree tops was adventurous fun of the most daring of boys.

It was plainly evident to the white settlers that the plum orchard was not a growth of nature only–but had been planted and that it has been a meeting place of the Indians for years. There were deeply worn paths leading to it from the western hills and from the river banks. The very early settlers told of Indian “pow-wows” with feast and ceremonies and of a wigwam – so hedged about by trees and covered with grapevines, that neither snow nor rain, the cold blast of Winter or the heat of Summer could penetrate.

A fireplace of stones occupied the center of this wigwam–a hole being left above for the escape of the smoke. At one side was a bed made of poles. In the early Spring days many Indians came to the Rapids of the O-wash-ta-nong with their Winder trapping of furs; the squaws with find baskets, beautifully beaded moccasins of smoke-tanned buckskin, which they desired to trade for the Che-mok-a-man’s (white man’s) food or clothing.

There came to our home one day a squaw with a lack of baskets. She wanted to trade a basket for a piece of salt pork and a loaf of bread. In broken English and with many gestures my mother was made to understand that a squaw and baby papose were very sick and were in the wigwam in the plum orchard. My mother went with the squaw to the wigwam, more than a mile away, carrying things for the mother and her little baby and that evening the writer, with a boy chum, peddled down the river in canoe, with a basket of food our mothers had prepared. In the fireplace was a small fire over which a kettle or water was steaming. The old squaw brought in an armful of drift wood to build up the fire and light the wigwam. The basket was quickly unpacked and food given to the Indian mother, who was reclining on the pole bed made comfortable with a mattress of grass. When fed, she closed her eyes in sleep, the little papoose snuggled lovingly in her arms.

Outside the whippoorwilla were calling, other night birds kept up a plaintive song, while from the river banks the frogs made endless croaking. Boy-like we lingered and begged for an Indian story–for a story of the plum orchard and sitting on the ground at the side of the pole-bed, with half closed eyes the old squaw began to talk.

“I will tell you as my mother told me–as my mother was told–as my fathers talked many as the fires in the sky.”

The Legend of the Indian Plum Orchard

“Man-a-boo-sho, the creator of all–He came from the home of the Sun God with heavy pack upon his back. He was weary, he had travelled far. He had created many things, He had danced many songs. He has sang many times to the birds his children. He was happy.

Here I will rest, all is well. He took from his shoulders the pack, it was heavy. It had many things. He placed it by the waters, the O-wash-ta-nong. The waters sang to him, the waters made music, the waters said ‘rest my grandfather, you have travelled far,–here all come your children to rest, here shall you feast, here shall you dance.’ Man-a-boo-sho said; ‘I cannot sing the song of the waters.’ I will dance the song of the waters.’ He said to the birds, ‘I will dance that song.’ He lifted his pack, he walked in a circle, he walked many times, he made wide trail, he took from his pack many things, he placed them in the ground. Then came out of the ground small trees, they became large. Then came vines about the trees, then came fruit on the trees, some red, some yellow, then came fruit on the vines some blue.

The trees called “ho! ho! my grandfather. As we paint our fruit so shall the Indian paint his baskets. Ho ho, my grandfather you have danced. We have made you a wigwam. Here we ask you to live, you are weary you have travelled far.” While he had danced the Sun God had gone beyond the hills. The waters did not rest, they made song in the might to charm the Sun God back. The birds came to the trees for good and shelter. Man-a-boo-sho rested, he had travelled far.

The Sun God came again. Two squaws came, a mother, a daughter. They gathered vines and made a wigwam. They gathered grass and made a bed. And Man-a-boo-sho heard them not for the was weary. He had travelled far. The daughter rested in the wigwam, she was in pain. The mother called upon the Sun God to help the daughter. Man-a-boo-sho awakened, took from his pack red berries “Eat the fruit I have caused to grow, it is the squaw’s berry, it is the mother’s fruit.”

And the great creator placed many berries under the trees and about the woods. Then Man-a-boo-sho travelled far beyond the hills to the land where the Sun God goes.

The people of the woods came every year to dance the song of the waters in the circle of the trees. The moss makes a resting place. In the wigwam there is shelter for the mothers. The papoose cradle swings in the vines. Man-a-boo-sho comes often to visit his creations. Every year the Sun God comes. Every Summer the red, the yellow and the blue fruits come. Every year the waters sing their dance song. Every year the birds make their homes and the women of the woods, of the country, of the far-a-way waters come here to welcome the papoose. This is the place Man-a-boo-sho created for the Indian mother. He had travelled for, he had created many things.

The fire in the wigwam burned low. The old squaw looked with dreamy eyes into the slumbering coals. The mother and her papoose were sleeping. Outside the whip-poor-wills were calling as we paddled up stream home, without splash of paddle or spoken thought, lest the sleeping spirit of Man-a-boo-sho be disturbed.

'Draft text courtesy of the Grand Rapids History and Special Collections Department of the Grand Rapids Public Library'